The halls of the Louvre have long whispered tales of art, history, and the occasional mystery. Among the most haunting is the 1911 theft of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, an event that left a scar on the museum’s legacy. Though the painting was eventually recovered, many other stolen masterpieces have vanished without a trace. Now, a group of artists and technologists is attempting to rewrite this narrative—using artificial intelligence to reconstruct lost or stolen artworks. The question lingers: Can technology truly mend the wounds of history, or are these digital recreations merely elegant ghosts of what once was?

The project, spearheaded by a collective of digital artists and AI researchers, focuses on recreating paintings that were looted, destroyed, or lost to time. By training neural networks on surviving sketches, descriptions, and stylistic elements of the artists’ other works, they generate high-resolution approximations of the missing pieces. One such example is The Nativity by Caravaggio, stolen in 1969 from the Oratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo and never recovered. The AI’s rendition, while not perfect, captures the dramatic chiaroscuro and emotional intensity characteristic of Caravaggio’s work. It’s a tantalizing glimpse of what once hung in that empty frame.

Yet, the endeavor is not without controversy. Art historians debate whether these digital reconstructions dilute the authenticity of the originals. "Art isn’t just about the image," argues Dr. Claire Laurent, a professor of art history at the Sorbonne. "It’s about the physicality of the brushstrokes, the aging of the canvas, even the smell of the varnish. An AI can mimic the visual, but it can’t replicate the soul." Others, however, see value in the attempt. For museums and the public, these recreations offer a chance to engage with art that would otherwise remain inaccessible—a digital bridge across the gaps of history.

The ethical implications are equally complex. Many of the lost works were stolen during wars, colonial looting, or illicit trades. Recreating them digitally raises questions about who "owns" the new versions and whether they inadvertently sanitize the crimes that led to their disappearance. "There’s a danger of treating these reconstructions as replacements," warns curator Javier Mendez. "They should serve as reminders of loss, not as Band-Aids for historical injustices." The team behind the project insists their goal is educational rather than restorative—to spark dialogue, not to erase the past.

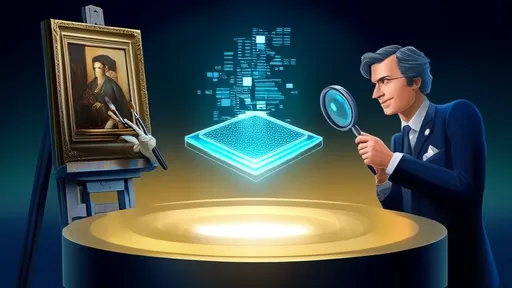

Technologically, the process is as fascinating as it is painstaking. The AI analyzes thousands of images from the same period, artist, or movement, learning to generate plausible details where information is scarce. For instance, when reconstructing Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee—stolen in the infamous 1990 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist—the algorithm referenced the Dutch master’s other seascapes, ship designs, and even weather conditions typical of the era. The result is a swirling, tempestuous scene that feels undeniably Rembrandt-esque, yet remains an educated guess.

Public reaction has been mixed. Some visitors to digital exhibitions featuring these works report feeling moved, even awed, by the reconstructions. Others find them unsettling, like encountering a doppelgänger. "It’s beautiful, but it’s not the painting," remarked one Louvre attendee. This dichotomy underscores a fundamental tension: Can art exist independently of its material form? For generations, the answer was no. But in an age where digital experiences increasingly mediate our relationship with culture, the lines are blurring.

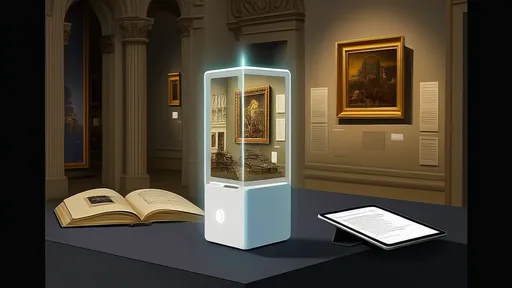

The Louvre itself has remained cautiously neutral on the project. While not officially endorsing the AI reconstructions, the museum has acknowledged their potential as educational tools. "Anything that reignites interest in art history has merit," says a spokesperson. "But these works are labeled clearly as interpretations, not originals." This distinction is crucial. The AI-generated pieces are not displayed alongside surviving artworks, nor are they presented as equivalents. They inhabit a liminal space—part homage, part hypothesis.

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of the initiative is its impermanence. Unlike physical restorations, these digital files can be updated endlessly as new data emerges. A reconstruction made today might evolve tomorrow with the discovery of a forgotten sketch or diary entry. In this way, the project mirrors the fluidity of history itself—always subject to reinterpretation. "We’re not closing the book on these works," says lead artist Sophie Renoir. "We’re adding a new chapter, one written in code and pixels."

As the debate continues, one thing is certain: Technology is irrevocably changing how we interact with the past. Whether AI can "heal" historical wounds remains to be seen, but it undeniably offers new ways to remember, to question, and to imagine. The stolen paintings of the Louvre may never grace its walls again, but in their digital afterlives, they continue to provoke, inspire, and teach. And in that, there is a kind of redemption.

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025